Jump-Start Copywriting

How David Ogilvy launched a sell-out advertising campaign

Even the best cars in the world need good copywriting. In 1959, an up-and-coming copywriter named David Ogilvy wrote an ad that was so good it literally sold out every Rolls-Royce in America and created an eighteen-month waiting list. This story — the story of Ogilvy’s most famous career-defining advert — is a textbook example of what professional copywriting can do for a business, even when budgets are tight.

The best car in the world: Rolls-Royce in 1959

In the late fifties, Rolls-Royce was already an established luxury brand. For a half-century, they had been selling hand-crafted cars to ‘top people willing to pay top money’ all over the world. Global elites like Henry Ford and Charlie Chaplin owned Rolls Royces — the prestige of ownership was high — but all was not well commercially. The British car maker had spent most of WWII building aeroplanes, and by 1959, it was facing stiff competition from Detroit’s motor industry. In the United States at least, Rolls-Royce was in danger of being forgotten.

Then David Ogilvy got involved.

A ‘peppercorn’ advertising budget

Ogilvy was determined to take on the Rolls-Royce advertising account, but his partners at Ogilvy, Benson & Mather were against it. Rolls-Royce had a miniscule marketing budget of $25,000. It was almost certain to make a loss for the agency, as their tiny commission on the $25,000 of billings would be swallowed up in creative production costs. What’s more, the budget was dwarfed by the ad spend of larger car makers like Ford and Chrysler.

To Ogilvy, none of that mattered: Rolls-Royce was one of the most prestigious brands in the world. He was determined to seize the opportunity with both hands. Ogilvy won the business, booked advertising in two newspapers and two magazines (the budget would stretch no further) then got straight to work on a career-defining sales message.

At the time, most of the ads produced by Detroit’s motor industry were stylish and charming, but they weren’t commercial. Car ads were meant to announce new car models to the general public — the ads weren’t expected to sell (selling cars was the job of the dealership). Rolls-Royce’s advertising was no exception; the Silver Ghost had been declared the “best car in the world” in 1906, and Rolls-Royce were still plastering this boast on every advertisement in 1958, over a half-century later. The claim was certainly impressive, but it did nothing to compel buyers to book a test drive.

Direct response copywriting

Most magazine and newspaper advertisements — especially for luxury goods — can be classed as brand advertising. Brand advertising is meant to ‘inform and remind’ — it’s there to keep a brand at the front of people’s minds. Direct response advertising, on the other hand, is much more commercial. With Direct response advertising, the goal is to get consumers to react to a compelling sales message in an immediate and measurable way. Direct response advertisements rely on offers, bullet points, calls-to-action, price lists and anything else the copywriter can think of to sell a product then-and-there, while the reader is looking at the advertisement.

In the late fifties, direct-response advertising was seen as a low-brow and ugly way to win sales. For a luxury brand like Rolls-Royce, it was downright inappropriate. Ogilvy was an experienced salesman and an avid student of direct-response advertising. He had seen what the direct response copywriting techniques could do for an advertising client. His job was to wring more sales out of his small audience than any of the big-budget car makers in Detroit — it was that simple.

Starting with research

There was no room for error. Every potential Rolls-Royce owner who read the Ogilvy ad would have to be convinced — on the spot — to book a test drive at their local dealership. To convince buyers so quickly and effectively, Ogilvy’s ad would have to be packed with compelling details about the car.

For three weeks, David Ogilvy learned everything there was to know about Rolls-Royce. He read every available technical document, industry report, magazine review and research paper. He personally visited the Rolls-Royce factories and spoke to engineers and craftsmen. He met with importers and dealers on both sides of the Atlantic. He wrote hundreds of pages of research notes. By the time he was ready to start work on the advertisement, he knew everything there was to know about Rolls-Royce.

The best headline in the world

Using his research as a guide, Ogilvy wrote more than one hundred potential headlines, then whittled down to a shortlist of twenty six. He passed his shortlist around to the other writers at Ogilvy, Benson & Mather and asked them to choose the one headline that they felt worked best. The line that everyone finally agreed on was eighteen words long:

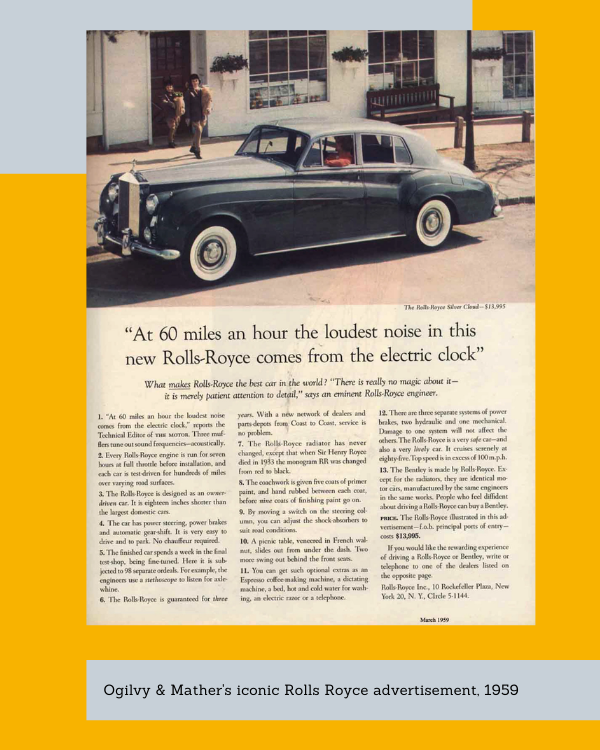

“At Sixty Miles an Hour the Loudest Noise in the New Rolls-Royce comes from the Electric Clock.”

This headline was a brave choice. It said nothing about pedigree, prestige, or the other intangible qualities of Rolls-Royce ownership. It was hard to say out loud in one breath. It focused on an inconsequential feature — an electric clock — and didn’t mention anything about the engine, bodywork or interior finishes of this world-leading vehicle. If Ogilvy had been working alone, he might well have dismissed the headline at an early stage of the writing process … but his trusted team of writers had told him that it was better than the twenty five other headlines he had presented.

Thirteen unique features

The headline was followed by long paragraphs of detail. In seven hundred words, Ogilvy explained how every new car engine was run for seven straight hours before installation, and how factory engineers used stethoscopes to ‘listen for axle whine’. Readers learned about the French walnut picnic table that slid out from under the dash, and how they could get ‘such optional extras as an Espresso coffee-making machine, a dictating machine, a bet, hot and cold water for washing, an electric razor or a telephone.’ Ogilvy listed thirteen unique features in all, followed closely by a brief matter-of-fact paragraph on pricing.

A simple, clear call-to-action

The last line of the ad simply said ‘If you would like the rewarding experience of driving a Rolls-Royce, write or telephone to one of the dealers listed on the opposite page’. It was a straightforward invitation to book a test drive, and it was arguably the most important part of the whole advertisement.

Every direct-response advertisement ever published includes a clear call-to-action like this, but at the time, big-brand advertising agencies rarely asked the consumer to do anything — especially if they were promoting a luxury product like Rolls-Royce. Ogilvy knew that this ad had to sell as many cars as possible – the test drive invitation would get car buyers to cross the threshold of their local Rolls-Royce dealership.

Selling every Rolls-Royce in America

In March 1959, Ogilvy’s Rolls-Royce ad went to print. The ‘peppercorn budget’ meant that his ad appeared in just four publications, but the ad was so effective that it sold out the entire US inventory of Rolls-Royce cars in a matter of weeks. In fact, the ad was so effective it created an eighteen month waiting list of new car orders. The Rolls-Royce factory couldn’t keep up with demand, and instructed Ogilvy to pull the advertisement.

Ogilvy achieved something nobody had ever done before: he wrote an advertisement that was so good his client had to stop using it.

A Lasting Legacy

Ogilvy’s 1959 Rolls-Royce advertisement was hailed by many — including Leo Burnett — as the ‘ best ad of all time’. In spite of its limited run, Ogilvy’s ad had such a massive impact on the general public’s perception of Rolls Royce as a quiet car that, in 1965, Ford based a multi-million dollar campaign on the claim that their car was “2.8 decibels quieter than a Rolls”.

The work made a lot of money for Rolls-Royce, but just as Ogilvy’s partners predicted, it didn’t produce much money for the agency. Nor did it lead to a particularly fruitful long-term relationship – Ogilvy resigned the account in protest when Rolls-Royce shipped five hundred ‘defective cars’ to the United States.

What makes this advertisement so special is not how many cars it sold, but how David Ogilvy created it. He researched his subject matter obsessively for weeks. He wrote hundreds of headings and thousands of words of descriptive text in search of the most convincing sales message. He invited the opinion of trusted colleagues and acted on their suggestions. And — most importantly of all — he made sure that the ad would do what it was meant to do: sell more cars.

Learn more about David Ogilvy, CBE 1911 – 1999

David Ogilvy was one of the best-known advertisers of his generation. He wrote two excellent books on advertising (Confessions of an Advertising Man and Ogilvy on Advertising), and a lesser-known autobiography (Blood, Brains and Beer). He was also the subject of a superb biography called The King of Madison Avenue by Kenneth Roman.